When I married in 1978 (stupidly young and it didn’t last….), I knew kitchens existed but wasn’t entirely sure what went on in them. I knew food emerged but had no idea how it happened. Didn’t do “Domestic Science” at school as I was in the stream that did Latin and French, both of which I have to say, have been remarkably useful. It now enrages me to think that learning to cook was (and might still be in some schools) regarded as less demanding than learning languages. Better I don’t get started on that one; it is probably a whole other post.

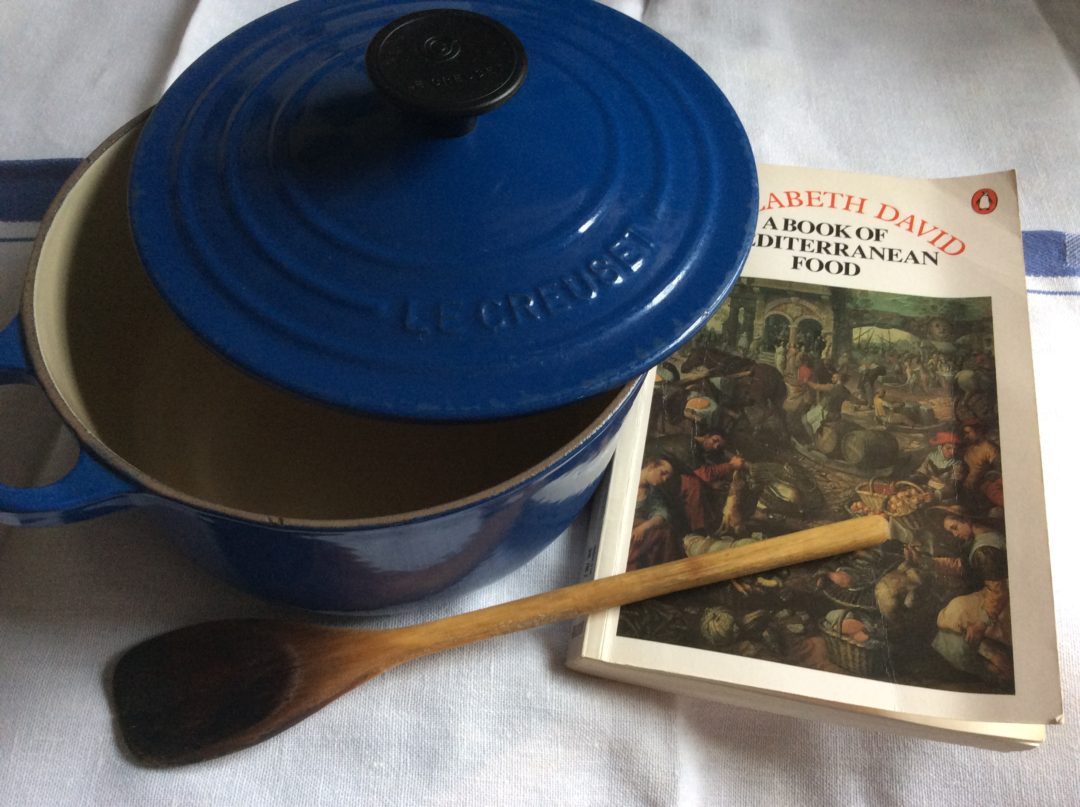

Shortly after becoming engaged my wise mother, fearing that my husband would have to live on toast, bought me the Delia Smith Complete Cookery Course, which in those days came in three paperback volumes. In truth, I wasn’t terribly impressed with that as an engagement present (what an ungrateful creature I was) but when I finally opened the first volume, something in me blossomed and food became an enduring passion. I am also terribly attached to some of the books and equipment that I bought or was given in those early days. I still have (see picture) the very first wooden spoon I was given and the casserole in the same picture is now over 35 years old and.

In some quarters, it is now fashionable to decry Delia and whilst I no longer cook from her books, she did teach me the basics, allowed me to start cooking edible meals (and then good meals) and for me, best of all, that edition included a Bibliography! One of my other passions is books and reading (to the point that when I met Edoardo, we realised that consolidating our homes would mean accommodating over 5,000 books), so pointing me to other writers and cooks was just bliss.

Now, for me, this is where a deep, enduring love of food, cooking and its social and political history started. The first person I investigated from Delia’s bibliography was Elizabeth David and for me, this was when I really began to understand flavours, textures and the simple joy of good food eaten seasonally with minimal interference. I think I was a little in awe of her in the way I never was with Delia, but I as grew older and matured myself, Mrs David’s (never, just never Elizabeth) approach to much in life resonated with me.

The second aspect of Mrs David’s writing that spoke to me was the sheer poetry of it. Should you doubt this, may I refer you to the first two paragraphs of her chapter on Fish in “Italian Food”. The description of the Rialto fish market takes me straight back there every time I read it. She makes me not just see it but smell and hear it, too.

It has probably also taken me some years to understand how brave Mrs David was to publish her first book in 1950 post war Britain, when food was still rationed and olive oil was something requested in the chemist’s to sort out wax in one’s ears. Can you imagine the reaction of people being asked to cook with something they regarded as medicinal? I also have huge sympathy for the early brave devotees of Mrs David – I cannot begin to think what it must be like to cook without olive oil, lemons, garlic, spices and fresh herbs; for those intrepid cooks, the frustration must have been enormous.

That first book, “A Book of Mediterranean Food” is still amongst my most referred to and certainly takes the prize for the most bespattered pages (none of my foods books is pristine – if I come across one it usually means it was rubbish and, no, am NOT naming names!). It is a continual source of inspiration, not dogmatically but as a jumping off point for interpreting her recipes.

There are points upon which I depart from her advice; for example, adding oil to water for cooking pasta is nonsense. It will just float there on top while the water boils away, doing its job and ignoring the oil. You are therefore wasting precious oil and thus money. I know there are people who swear by this, but I have never come across an Italian who does it and when I enquired, was met with a sigh of resignation indicating that the craziness of the British in the kitchen should never be underestimated. She also says pasta can take up to 20 minutes to cook. Nope, not unless you like wallpaper paste.

When she speaks of meat and fish, however, she remains for me definitive and whilst I have adjusted her recipes to suit my taste, her basic advice and method remain unaltered. As we approach the cooler months of the year, I’d like to share with you my version of her Daube de boeuf provencale. It is easy, if not cheap, but does serve 6, or fewer with left overs and smells utterly divine while cooking. It is a recipe that denotes for me the arrival of autumn, as I always seem to make it in September after the lighter foods of summer.

Daube de boeuf provencale

Print RecipeIngredients

- 1 kg top rump of beef, cut into squares about 7/8cm and 8mm thick (I always buy the beef in the piece and cut it myself to get the right sized pieces)

- 175g unsmoked streaky bacon or pancetta, sliced into strips

- 2 carrots, peeled and sliced into rounds

- 2 medium onions sliced into half moon slices

- 2 tomatoes, skinned and sliced (you can use tinned and then use the rest to make soup as a first course)

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 2 cloves of garlic, peeled and squashed under the blade of your knife

- bouquet garni (I use a piece of celery with a bay leaf, a generous amount of thyme and parsley and if possible, a large slice of orange peel, sans pith, tied up with kitchen string and anchored to the handle of the casserole)

- a (very) generous glass of red wine, French if possible, but use what you have

- salt and freshly milled ground pepper

Instructions

Pre-heat the oven to 140 degrees C/130 fan

In the bottom of a thick based, heat retaining pot (I use an ancient and much loved le Creuset casserole) pour in the olive oil, the bacon or pancetta, then the vegetables and then layer the meat slices, overlapping them slightly. Bury the garlic and bouquet garni in the centre.

Season and with an uncovered pan, start cooking over a moderate flame for about ten minutes

In a separate pan, heat the wine until at a lively boil and set it alight

Once the flames have died down, pour the bubbling wine over the meat mixture

Cover VERY tightly (I add a layer of tightly clamped tin foil before the casserole lid) and out in the oven for about 2.5 hours

I like to add pitted, black olives about half an hour before the end of the cooking time

It might not seem that you start with much liquid here, which is true, but long, slow cooking will produce a fragrant, delicious dish for so very little effort.

Although I am usually all for saving on the washing up, I do like to serve this in the traditional way on a wide shallow platter, having extracted the bouquet garni, poured the sauce around the meat and garnished with persillade of finely chopped garlic and parsley, or a few capers and a couple of chopped anchovies

This goes well with wild red rice or plain boiled potatoes

Notes

As there is no pre-browning of the meat, this is wonderful for a slow cooker, but do try to find time to flame the wine. I have to confess that I have on occasions made do with just heating the wine, as I am not always at my brightest before my first cup of coffee in the early morning. Flames in my kitchen prior to coffee is a tad alarming for me. Anyway, the upshot is that it is subtly different without the flaming trick, but not worse. Just different.